From the security crisis in the Sahel to the migration flows in the Mediterranean, from past and present civil wars to wildfires and flooding in Europe, a specter is haunting policy-makers: the spectre of climate change. International organisation and states have now decided to take this issue seriously and are proposing and implementing big projects (from mega-project to various forms of cooperation) to confront this existential threat. As repeated by practically all the leaders at the last COP26, climate change is not just an ecological problem but is a threat to the very existence of mankind itself, but is it all so linear? For a better understanding of climate change and its links with conflicts and security practices, we posed some questions to Tor A. Benjaminsen, professor of Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Professor Benjaminsen has analysed environmental change and land-use conflicts through the perspective of political ecology with a special focus on ‘desertification’ of West African Sahel, the jihadist insurgency in Mali, and environmental conservation in several countries in Africa. He is also a Lead Author of the 6th Assessment Report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

After the publication of the last IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report, it seems that we have reached a sort of global consensus on the existence of Climate Change as an empirical fact. Do you think that the intellectual debate between believers and deniers of climate change is now over?

I’m not so concerned about climate change denialists. I mean, the evidence about climate change is very clear and has been clear for some time. In this sense, what is important to underline about the last IPCC reports is that the Panel has become increasingly more certain about its findings. Consequently, what we have seen is that very few, if any at all among the governments or policymakers in general have questioned the very existence of climate change. It is happening, so I don’t think that’s really a question anymore. Beside the empirical evidence when we talk about climate change in the political debates of course it is obvious that some arguments from the denialists will be around in the future and will be used by some people, but at the same time it seems that the main global actors have all accepted that climate change is real and that it is a serious threat.

You’ve been skeptical about the mega-projects to mitigate climate change, such as the Great Green Wall initiative in the Sahel, why?

Yes, there are several things that don’t convince me about the Great Green Wall indeed, and some of them are also typical of these mega-projects about climate change. What we have seen so far with the implementation of the Great Green Wall is how the project has been implemented mainly in Senegal, where trees have been planted on pastureland, dispossessing pastoralists, preventing them from accessing pastures they have been using historically. This leads to another aspect that I don’t like about mega-projects, that is the relationship with local communities: we haven’t seen any involvement of those, most evidently pastoralists, in the project. As a consequence, it is evident that with the progressing of this project, more people will lose access to land and natural resources. Above all, the use of land and resources is increasingly determined and regulated by external actors such as international organisations, NGOs, or even the state itself. Finally, I find it deeply ironic that one of the aims of the Great Green Wall is to reduce migrations and also to reduce the recruitment to jihadist groups, but how can the Great Green Wall help to achieve such objectives if it leads to the dispossession of pastoralists? I fear that the result may be the opposite of what is intended.

Donors say that the Great Green Wall is not just about planting threes anymore, but also about empowering local communities…

I’m fraid, things are more complex than shifting from planting trees to empowering communities. This project has originated as one focused on the northern part of the Sahel, at the border with the Sahara. Now, there is a long experience with tree planting projects in that area. We know for sure that it takes a lot of work only to have the trees to survive. Moreover, this idea of planting trees as a necessary step is based on the assumption that the desert is advancing, but this hasn’t been the case since the drought of the 1980s. On the contrary, the Sahel has become greener and there has been a lot of natural regeneration going on in the Sahel. The Gourma region in Northern Mali, which I visited for the first time in the late 1980s has much more trees now than it had at that time. My first research in the area included studying aerial photographs and if you look at the images from this area now you can clearly see how the density of the trees is currently much higher than it was in the 1980s. And this is not unique to this area. There has been an extensive natural regrowth of plants and trees in much of the Sahel. Consequently, there is something wrong with the assumption behind this Great Green Wall project. Of course, I am not against the idea of planting trees in itself, but we should question whether this an actual need of the locals. This leads to another problem of these big projects based on top-down approaches, more specifically, they fail to pose an honest and straightforward question from the beginning: what is the problem? What is the problem that we want to address? In the case of the Great Green Wall, for instance, there are many different problems that its proponents want to solve with one package. One perceived problem is that the desert is advancing, another problem is climate change in general, then there is the problem of migration and then there is the recruitment by jihadist groups. So, we take all these problems, and we try to solve them all with one initiative. Honestly, I don’t think that is possible. We have to be very clear about the problem first. My colleague Boubacar Ba and I have written about the main reasons why pastoralists join jihadist groups, and marginalisation appears to be one of the key reasons. Pastoralists are losing power; they are losing access to land, and they are losing access to natural resources. They have become frustrated or disillusioned with the state as well as with the elites in general. As a consequence, when jihadist groups come along, they may think that it cannot be worse than a state perceived as corrupt. It is purely circumstantial that this resistance is linked to Islam. If this situation had materialised in the 1970s or 80s, the same resistance might have adopted another “liberation ideology”, such as Maoism for instance.

Is it appropriate to say that we are witnessing a “securitisation” of climate change? If so, how do you think this is taking or will take shape?

Climate change has been discussed as a security issue, most notably within the UN Security Council, for at least 15 years, so from a diplomatic perspective there has definitively been a securitisation of climate change. Taken as an argument or an issue more generally, climate change serves different political purposes. On the one hand, a more or less direct link between security and climate change is used to capture the attention of policymakers and the international community at large, to raise awareness on the seriousness and the necessity to act on this issue. The downside of this specific securitisation of climate change is that it is often convenient for the ones who are responsible for the violence. When Omar al-Bashir, the former president of Sudan, heard that according to some hypotheses the Darfur conflict was caused by climate change, of course, he got a big smile on his face. There are also claims that the civil war in Syria might be linked to climate change, and probably Bashar Al-Assad is very happy to hear that.

So basically, the link between climate change and conflict helps to remove political responsibilities, like: “it’s not my fault, it’s climate change. Without it, there wouldn’t have been any war”.…

Yes, climate change works to depoliticise conflicts.

Does this mechanism work for jihadist groups as well?

No, I don’t see that working for them. Jihadist groups are more interested in politicising conflicts or putting their claims forward in some ways.

Most studies on climate change and conflict are now focused on the so-called Global South even if this phenomenon is increasingly affecting the North. Why is it the case?

I think we should start exactly from this question: why is this climate change and conflict link only used, or mostly used, in analysing countries in the Global South? Because you know, we have conflicts in Norway or northern Europe as well, which are usually not blamed on climate change even if climate change is manifest here as well. I guess that this happens because here we know the context in the countries we come from, and we know that even if climate change is real and it is a serious issue, it is not the cause of these conflicts. Even if climate change might have played a role, we know the politics and history of those conflicts, and we know it would be absurd to claim that climate change has caused them. But when discussions focus on faraway places of which we ignore the history and the politics, it is easier to draw on general narratives. It is a sort of orientalism in a way, and a kind of environmental determinism, which is put to use when one is not really interested in knowing the history or understanding the politics of certain places.

You’ve researched extensively the link between climate change and conflict in Mali. What are the main lessons that we can learn from this case study?

One lesson is definitely to take pastoralism seriously as both an economic activity and a livelihood. I don’t think it is taken seriously today, neither in the Sahel nor in Europe. Indeed, I think this is a global problem. We have pastoralists here in Norway, the Sámi reindeer herders. What is interesting is that we see the exact same problems in Norway with the relationship between Sámi reindeer pastoralists and the state that we also see in the Sahel. So the relations between governments and pastoralists are not just an African problem, but a global one.

What you’re saying it’s interesting because we also know that we should consume less meat and that we should, by consequence have less livestock or progressively abandon pastoralism to fight climate change.

You see, I think there is a certain degree of confusion on this issue. It is important to distinguish between industrial meat production and this free-range meat. Also, there are studies, which clearly show how pastoralists have a very light carbon footprint, and this difference leads me to another point: context. Contexts are crucial to understand conflicts. You need to study the history and politics of the place. I am now reading a book by a French anthropologist, Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan titled La Revanche des Contextes (the Revenge of Contexts) which is about why development policies, programmes or projects fail. It is often for this same reason: those who design these initiatives forget or ignore context specificities. I understand that it is occasionally easier for policymakers, government officials and donors to go for a more technical approach and copy-paste projects taken from elsewhere, rather than focusing on understanding context specificities and adapting to those.

You’ve said that political ecology is, in your opinion, the best framework to analyse conflicts, but what are the main limitations of this approach in your view?

Political ecology has been criticised for only being a critical approach, that is: it is not about providing solutions, but more about providing critiques. I have some sympathy with that argument, but on the other hand, I genuinely believe that in order to change things for the better, you need to understand what went wrong first. You need to have a good analysis before you start to do things in practice.

Some people argue that political ecology is based too much on qualitative methods, while climate change should be discussed with cold numbers and hard facts. Still, we have had numbers on climate change for a very long time and this hasn’t worked to reach a global consensus on climate change, nor in providing solutions

Yes, there is this kind of critique, but there is actually a certain use of quantitative methods as well, at least in some political ecology. I personally rely on mixed methods. Even if you look at the IPCC, we are now on the sixth assessment report and especially since the third there has been an increasing involvement of social sciences and qualitative methods among the IPCC authors. So there has been a realisation that we need more social sciences to understand climate change, because it is not only about numbers and how the climate is changing. It is, again, about understanding contexts and understanding how societies can adapt or mitigate this problem. In the end, it’s important to take into account the existence of different methodologies, but the most important thing is about using these methods wisely and to know their limitations.

To what extent is population growth a relevant factor when analysing climate change or the link between climate change and conflicts?

Some people say that overpopulation is like the elephant in the room in the climate change debate, but I tend to disagree with this at least for two reasons. First, I think that this factor is not actually ignored. On the opposite, it is discussed quite extensively, especially in the media and policy circles. Secondly, while I do believe that population growth is a relevant factor, I also think that its impact varies considerably depending on the context. This often leads to exaggerating the concern about population growth, especially when the alleged linkage between climate change and conflict is discussed. Generally speaking, in the cases that I have studied, I have concluded that population increase may play a role, but that other factors are generally more important. Our findings suggest that when conflicts escalate, it is always related to external or internal political factors rather than changes in demographic variables.

So, population growth can be another case of de-politicisation or de-responsibilisation?

Yes, because when you don’t study contexts, it is easier to blame the problem on climate change, population growth or ethnicity. I don’t say that we shouldn’t be concerned about population growth, but I believe that, as it is presented in the policy and media circles, it is overestimated. I mean it can play a role, but each conflict ultimately depends on its context.

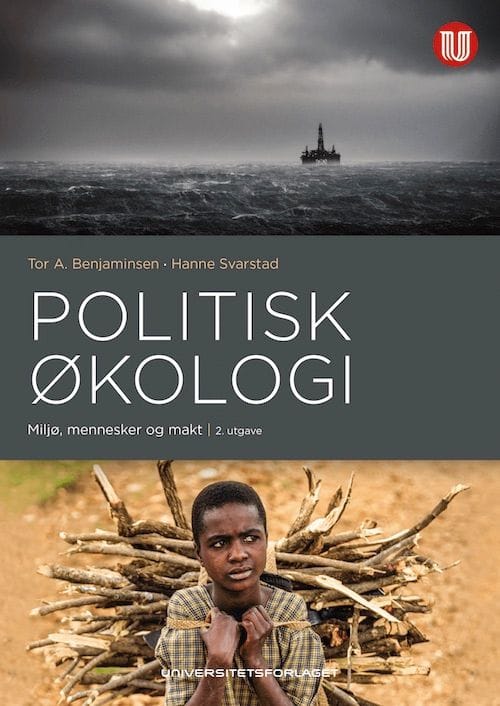

Cover photo by Frieda Mikulcak, a herder in Germat (Agadez), Niger, (CC) 2009.